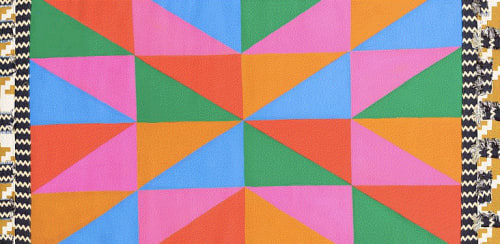

The new MOCA Los Angeles exhibition, With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985, is a maximalist delight to behold. Replete with feathers, glitter, embroidery, quilts, wallpaper, and other such explosions of expression, the works included pay collective homage to decorative arts from all over the world.

But taking delight in ornament was more than an aesthetic choice for participants in the pattern and decoration movement, often referred to simply as P&D. Some experts even credit its collective outburst of creativity as the first artistic movement developed by a majority of female artists. Women like Miriam Schapiro, Joyce Kozloff, and Cynthia Carlson, who were just as interested in feminism as they were in breaking down the hierarchy of fine art of the 1970s, were the individuals who made it happen. “What had ruled the day—and I’m being glib when I phrase it this way—was the cool, gray minimalism that was sanctioned as true art and gerrymandered to include only those who were white and male,” exhibition curator Anna Katz explains of the movement's origins, when speaking to AD PRO.

Sound familiar? It's a sentiment that rings true within the context of our own time—not just in light of a resurgent interest in maximalism, but also in terms of the current cultural and political climate. In the ’70s, P&D artists weren’t interested in traditional hierarchies. Instead they embraced the patchwork quilts and floral motifs often demeaned as women’s imagery and turned them into expressions of gravitas.

Jane Kaufmann didn’t sleep under her colorful beaded crazy quilt—she hung it on a wall with the grandeur of a painting. The work uses over 100 different types of stitches as an homage to many generations of anonymous women whose handicrafts did not merit the attention of fine art. Cynthia Carlson applied her floral wallpaper installations—symphonies of color, pattern, and stencils—to walls by filling pastry piping bags with paint and using them to create decorative swirls. The finished piece defied the idea that likening art to wallpaper was an insult. Miriam Schapiro took the kitsch appeal of a heart and transformed it into an eight-foot abstract painting, part of a body of work she called femmage. A portmanteau term that combines the words female and collage, femmage codified women's practices of interior decoration, sewing, and scrapbooking into a forceful visual presence.

Photo Credit: Roman Dean